Foreigners Everywhere from Venice to Japan

Also, Jukebox dance show Illinoise moves its sold-out run to Broadway this week!

Greetings from the 2024 Venice Biennale exhibition, where this year’s theme is Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriana Pedrosa. The Central Exhibition (as well as a number of the national pavilions) explores otherness and life on the margin, mainly by showcasing the world’s indigenous, immigrant and queer artists. So the American Pavilion has chosen Jeffrey Gibson, a queer Choctaw and Cherokee artist, as the first Native American to get a solo exhibit in the pavilion’s 94-year history.

Brazil’s pavilion, renamed the Hãhãwpuá Pavilion after the traditional Pataxó name for the vast territory, showcases pieces from indigenous artists that explore the centuries of resistance to colonization conquered by Portugal.

And notably, the winner of the Biennale’s Golden Lion was Archie Moore, a First Nations Australian artist whose austere exhibit consists of family tree of 65,000 years drawn in chalk and a huge obsidian-colored platform covered with stacks of government documents relating to the deaths of Indigenous Australians in police custody.

The Biennale runs from until November 24, 2024. If you can find an excuse to stop in Venice (even for a short period), you’ll experience a spectacular exploration of art around the world and of the past.

Inspired by this Biennale’s foreigner theme, our next curation comes from Bea Phi, a member of the Writing Atlas who will be graduating from college in June. Of course, this is a very bittersweet time for them, and it makes them wonder what the heck all of this studying has meant. They’ve forayed in various literary spaces in the last few years, and Writing Atlas is one that they’re happy to consider one of their homes. Here, they recall their love and fondness for literature while probing some of the bigger questions about its worldliness—join them on a magical mystery tour of translation from America to Asia and back.

“Literature: Where in the World Are You?” by Bea Phi

In two months, I will graduate with a degree in Comparative Literature and a minor in Creative Writing. As far as written work goes, I have almost nothing to show for this, other than a few essays here and there on various topics, including but not limited to Jack Kerouac’s confrontations with the haiku, Korean activist poets during Japanese occupation, and a Heideggerian reading of The Brothers Karamazov. When asked about what it is that I’m studying, it’s hard to give an answer. It’s even harder to give an answer that isn’t immediately rebut with, “Well, why not English, then?” I suppose now, then, is the right time for me to endeavor on something deeply relevant to my own interests in the matter, though I first have to trace a history of the past year.

Last fall, I took the Introduction to Comparative Literature class that was required for all incoming majors to the department. It was strange, as I was already in my senior year. There I was, fathoming the fundamental question about a field of study which I had already dedicated a few years of my life toward. We read the basics: Erich Auerbach, Frantz Fanon, Jacques Derrida, and so on. One of my peers, also a senior, called it “remedial.”

These were the fundamental questions, which I ultimately found helpful to pose in the present: what does it mean for literature to be compared (which implies the existence of two things worth comparing), and moreover, what does it mean for literature to be worldly?

I believe I’m interested in the second question more so. The first appears more so as a formal consequence of the first. Years before, in the fall of 2021, I had come in with an interest in East Asian literatures and cultures, spending much of my time—inside and outside of class—thinking through translations of Japanese, Korean, and Chinese works. As an Asian American born and raised in the West, it was inevitable that I would have to confront these works in some removed context.

Around that time, I’d read “Detective Dog” by Gish Jen in The New Yorker (full text here) for a class with visiting author Andrew Sean Greer. This is a story that spans Hong Kong, Vancouver, and New York at very felt times in history, whether it was the 2014 Hong Kong protests or the more recent COVID-19 pandemic. There’s a Scheherazade-esque quality about it, where the mother Betty tells her son Theo about all of this, her difficult upbringing and the history she had been a part of. It made me think about what it meant as an Asian American to be interested in the work of storytelling.

It goes without saying, but “Detective Dog” is a story that quite literally couldn’t have been written at any other time. There simply wouldn’t be the sense of immigration which allowed Betty to leave Hong Kong, scrape some money together in Vancouver, and move to New York where she then raised Theo. There also wouldn’t be the sort of assimilation which gave Betty the name Betty, or her father Johnson having been given the name Johnson, despite them having been born and raised outside of America. Of course, worldliness is not without its reactions. In Vancouver, Betty faced an outcry of racism which still persists today:

“The Chinese are taking over,” they said. “The Chinese are buying up everything.” That was when they weren’t yelling, “Go back to where you came from!”

Asian American fiction, which is a relative newcomer to literature, is something that is inevitably interwoven with histories of immigration and—for some, like my parents—evacuation. There’s so much more that comes with this: violence, discrimination, alienation, and so on. Our very stories are global, transnational, and comparative in that way, as the result of being between places. It’s something like a far cry from the worlds of John Cheever, Raymond Carver, or John Updike, wherein one’s world is no much larger than the municipal demarcation of an American suburb.

I’ve been thinking about movement a lot lately because, for a workshop class, I was asked to present on a story from this year’s Best American Short Stories curated by Min Jin Lee and, of course, our friend Heidi Pitlor. I chose Maya Binyam’s “Do You Belong to Anybody?” from The Paris Review (full text here). This story takes place entirely in movement, whether it’s the movement of a plane from airport to airport, a taxi from stop to stop, or a person walking down the sidewalk of a strange and unfamiliar city alongside traffic. The title becomes a harrowing reminder of what it’s like to inhabit this world and all of its complications.

One review, that I still laugh at from time to time, said that Pride and Prejudice was “Just a bunch of people going to each other’s houses.” Well, if that were true, then I suppose worldliness can make things much more interesting. There are more places to move. There are more ways to move. There are more reasons, as well as consequences, behind the decision to move. Is literature, really, just about movement? In that case, I suppose now, more than ever, is a particularly exciting time for literature. One has to look no further than Binyam’s story to see why.

In addition to place and placelessness, diasporic literature is also concerned with language. The page becomes a place where multiple languages can inhabit, simply because they inhabit that place in our lives. We come from bilingual households, and there’s an in-between-ness about that too. Language has a way of itself moving but also perhaps being stilted in movement. This is something that readers can certainly notice. In the book Native Speaker by Chang-rae Lee, dialogue is sometimes rendered in English, other times in Korean. As readers, we feel the protagonist Henry’s torn-ness between cultures. To translate or not to translate thus is a writerly, sometimes editorial, concern. It itself can represent a conflict.

This becomes very much obvious—perhaps essential—when we bring in Asian fiction, not just Asian American fiction. Throughout my studies, I’ve thought carefully about what it meant for a work to originate in one language and be transplanted into another. I’ve thought even more about how delicate this procedure is especially for two languages seemingly disparate, such as Japanese and English. This procedure isn’t merely linguistic but also took on social, political, and cultural concerns. America is just a much different place from countries like Japan, South Korea, and China. History becomes a very complicated thing at the evocation of these names in the same sentence as one another.

A few months ago, I took a seminar which all seniors in the Comparative Literature department were mandated to attend. It was there where I presented on Banana Yoshimoto’s Kitchen, a bestselling novel in eighties Japan and abroad, rife with so much banal yet magical consideration in its matters of everyday life, yet also riddled with several problems in translation. In a class I had taken, in 2022, on modern Japanese literature and culture, I learned that Kitchen was notorious in the translation community for being a uniquely horrible one.

This book had meant so much to me a few years ago. Still today, it does. It felt like a revelation having stumbled upon it and read it. I’ve read it close to ten times now, and it still retains its charm. Over and over again, I was being told that it was a linguistic horror. While I felt some stiltedness in its prose before, I didn’t think it was bad. However, in an article harshly titled “How the English Language Failed Banana Yoshimoto” by translator Eric Margolis, one can look at how Yoshimoto’s casual and conversational tone sometimes becomes unwieldy and long-winding from Japanese to English:

The original, per Yoshimoto: “負けはしない.”

The literal translation, according to Margolis (and myself): “I won’t lose.”

The actual translation, rendered by Megan Backus: “I won’t let my spirit be destroyed.”

In my journey as a student, Kitchen has since served as an important example—both to me and now others I’ve spoken with—of how translation, or the worldliness of literature in general, is something that can be acutely felt. When done poorly, it can remove us even further from the work and deny us the gravity of it entirely. When done with an agenda, it can remake the work as well, for better or for worse. In Haruki Murakami’s novel Dance Dance Dance, the translator Alfred Birnbaum renders the following line:

“Before noon I drove to Aoyama to do shopping at the fancy-schmancy Kinokuniya supermarket.”

It’s that line which Herbert Mitgang, in The New York Times, asks, very funnily enough: “Wonder how you say fancy-schmancy in Japanese?” That leads us down a rabbit hole about Murakami’s very particular entourage of translators and publishers in the west, as well as the decisions they’ve made to make the Japanese writer’s work legible to an American readership. This rabbit hole is thrillingly chronicled in the book Who We’re Reading When We’re Reading Murakami by David Karashima. It’s certainly worth a read.

I’m just thinking a lot about worldliness these days. Of course, this isn’t just a quality that appears in literature. Another favorite example of mine is the scoring of Wong Kar-wai films. There’s something fantastic that happens to me when I hear a jazz song overlain on scenes set in Hong Kong’s cha chaan tengs. It’s that fantastic-ness which drives the musician-then-actress Faye Wong, in Chungking Express, to visit California on a whim, hoping to see what the real California was like, if it was anything resembling the kind of place that The Mamas & The Papas’ “California Dreamin’” imagined.

On worldliness, I suppose one final story that occurs to me now is another by Murakami, though I suppose it’s lesser known, having first been published in Granta before its gathering in the First Person Singular collection. In “Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova” (full text here), a man recalls a piece he had written in for a university’s literature magazine, which was a review of the Charlie Parker album Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova.

Of course, such an album doesn’t exist in our real world, and whether it exists in the reality of the story is something which the story seeks to uncover. The man remembers how he had stumbled upon the dubious record in a downtown Manhattan shop. Unconvinced of it, he left the record store without having bought it. Later, he returned in search of it again, but it was nowhere to be found. When asked about it, the owner of the record store said that such a thing had never existed. Our protagonist later has a dream in which he meets Charlie Parker himself, and the whole thing feels bizarre and fantastical.

This is textbook Murakami: his usage of dreams, his interest in music, and his tones of melancholy, loneliness, and surrealism. One of my friends, an astounding pianist and devotee to the form of jazz, thought the short story was deeply compelling. Two years ago, we discussed the incredulity of the story for a bit, as we drove in our third friend’s car, heading down El Camino Real in Palo Alto for a bite to eat. It made him think, “Oh, well, what if Charlie Parker really did play bossa nova? Wouldn’t that be interesting?”

I feel that there’s something magical about all of this when I think back to it now: three kids from Oregon, Indiana, and Minnesota, spending an afternoon in the San Francisco Bay Area, all to talk about a Japanese writer’s story translated to English, concerning a record shop in New York, wherein there may—or may not have been—a record from a Kansas City jazz musician playing the Brazilian music of Antônio Carlos Jobim. There’s so much movement needed in order for this conversation to happen.

In a few months, we’ll be moving even more—to our different places across this world, which has become such a big and vast thing in this century—and I guess there won’t be an occasion which we’ll get to talk like this about literature. I’ll certainly miss it. Whatever “it” is, I suppose that, then, is really the spirit of what I’m interested in.

Bea’s Favorite Emoji: 🤓

If you’re on TikTok or Instagram, you’ll know the untold horrors that 🤓alone has wrought upon intellectual culture and productive debate. (That’s, of course, assuming that social media has ever been a plausible venue for those …) This emoji, paired with the phrase “It’s not that deep,” has proven to be an unstoppable force to anyone who shows even the slightest interest or investment in something online. In fact, a kid has petitioned Apple to redesign this emoji on its keyboards, as it has caused him great distress.

Bea’s Favorite Wikipedia Article: X-Seed 4000

I love the genre of history concerning buildings-that-never-were. In my freshman year, I’d taken a class wherein I had to read the works of , the French postmodern architect who, in some ways, may be responsible for the angular and geometric nature of many buildings today. Since then, I’ve been hooked on the boundaries we can push with regard to building things.

Here’s one building, along with the currently-speculative, soon-reality project of The Line, never fails to amaze me. The X-Seed 4000 is a hypothetical Japanese city that could house up to a million people, requires millions of tons of steel, and stretches up to two and a half miles high in the sky. It would cost almost two trillion dollars to build. Some more fun facts: it would’ve been built along the Ring of Fire, it would’ve used bullet trains for internal transportation, and it would’ve required its own internal regulation to protect inhabitants from … well, mere meteorology. Finally, it was hypothetical from the beginning, nothing more than a firm’s concept for a “futuristic environment.” It was meant to be only dreamed of.

Bea Phi (they/them) is currently a senior at Stanford University, class of ‘24, studying Comparative Literature and Creative Writing. They serve as a Student Worker in the Creative Writing Program and a Peer Advisor in the Department of Comparative Literature. On occasion, they work on plays in the Asian American Theater Project on campus. They also work as an Associate Editor of Online Resources for Poets & Writers and have previously worked as an intern for the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. Time and time again, they join the Writing Atlas team on its brief adventures.

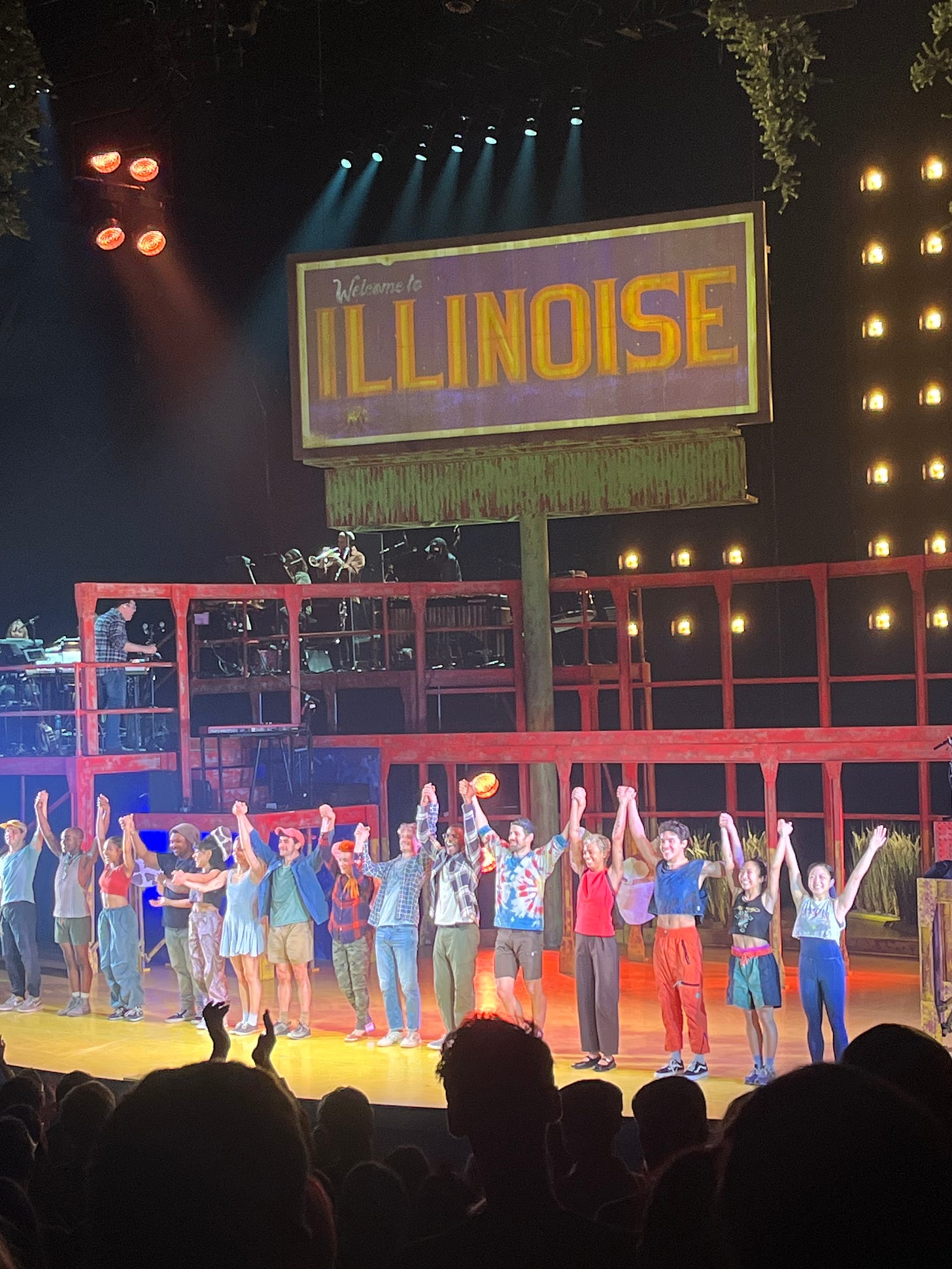

Welcoming Illinoise to Broadway

This weekend the musical Illinoise opened on Broadway, featuring some friends of Writing Atlas in the cast (shoutout to Byron Tittle and Dario Natarelli!). Based on the acclaimed 2005 concept album of the same name by Sufjan Stevens, the show is a musical, yes, but its focus is dance. Conceptualized and choreographed by Justin Peck (who did the choreo for the Spielberg West Side Story), there’s zero dialogue in the show, but the unique style of the dance (blending lyrical, Peck’s distinct sneaker ballet, tap, and musical theater) as well as the incredible staging create impressive feats of visual recognition, turning just a few props like a steering wheel, two lights, and a board into a car.

Writing Atlas caught it a few weeks ago (after waiting in line and some help from friends) during its sold-out run at the Park Avenue Armory (a must-see historic venue), just at the time that the show announced it was heading to Broadway. The show is incredible—Variety called it “one of the most singular productions in recent Broadway history”—and it pushes what a Broadway show can look like as it blurs the lines between jukebox musical and dance show. Its Broadway run at the St. James Theater is 16 weeks only—we’d highly recommend.

Where in the world are you, Writing Atlas fam? Let us know, and we might just let you have a shot at curating short stories and dispatches for us. At Writing Atlas, we’re always looking for new stories and cool moments to highlight! If you ever would like to curate stories, or share quirky photos, foods, cool places to visit or roaming stuffed animals with the community, please let us know by leaving a comment or otherwise reaching out to us! As always, keep visiting our Writing Atlas homepage as we keep rolling out exciting changes and updates!

Sincerely,

Your Writing Atlas team

“If there is no struggle there is no progress” is stunning! You’ve inspired me to look more into Jeffrey Gibson’s work.